Introduction

Embark on a journey through the UK’s landscapes, exploring the nuanced world of native uk plants. From pre-ice age survivors like Wood Anemone and Dog Rose to the influences of civilizations like Romans and Normans, discover the intricate botanical tapestry. Unravel the mysteries of plants often misconceived as native, challenging the boundaries of nativity.

Define what constitutes a native plant, navigating historical complexities and evolving landscapes. Explore the coexistence of native and non-native plants, dispelling the myth that only natives benefit wildlife. Meet non-native pollinator-friendly plants like Lavender and Buddleja, contributing to biodiversity without invasive concerns. Join us in unravelling the captivating stories of native plants in the UK, where history, ecology, and botany converge.

Definition of Native UK Plants and its Application

The term “native” holds a nuanced significance in the realm of botany, reaching beyond simple geographical boundaries to encapsulate a plant’s intricate historical relationship with a specific region. While geography is a factor, the designation of a plant as native considers its enduring presence and adaptation to the local ecosystem over an extended period.

This nuanced definition becomes essential in unravelling the intricate and often fascinating narrative of native uk plants in the United Kingdom. It prompts a deeper exploration into the historical and ecological connections between plants and the regions they inhabit, revealing a dynamic interplay between flora and the landscapes they call home.

The Ice Age Theory

The captivating theory that unfolds in the botanical narrative suggests that the criterion for true nativity in the United Kingdom hinges on a plant’s presence predating the formidable ice age. This geological epoch, a monumental chapter in the Earth’s history, unfolded approximately 2.4 million years ago, shaping the British Isles through sweeping glacial advances. The profound impact of the ice age left an indelible mark on the landscape, sculpting terrain, and influencing the composition of flora that could withstand the challenges of this icy era.

During this epoch, glaciers advanced and retreated, creating a dynamic and ever-changing environment. The climatic fluctuations, accompanied by ice sheets and extreme cold, posed a formidable test for plant life. Only those plants that possessed extraordinary resilience and adaptability could endure the harsh conditions and lay claim to being true native uk plants in the context of this theory.

The legacy of the ice age endures in the botanical tapestry of the United Kingdom, as the surviving plants not only weathered the glacial challenges but continue to thrive in the present landscape. Exploring the pre-ice age natives provides a fascinating glimpse into the botanical survivors that have stood the test of time, their endurance becoming a testament to the enduring interplay between geological forces and the resilience of plant life.

Pre-Ice Age Native UK Plants

With roots dating back millions of years, these plants not only withstood the frigid onslaught of the ice age but continue to grace the UK’s modern landscapes, weaving a botanical tapestry that connects the past to the present. As we delve into the individual stories of these pre-ice age natives, a fascinating journey unfolds, offering insights into the rich history and tenacity of plant life in the British Isles.

Wood Anemone (Anemone nemorosa)

This delicate and dainty flower emerges in woodlands, enchanting observers with its white blossoms that herald the arrival of spring. The Wood Anemone, with its graceful appearance, often forms charming carpets on the woodland floor, creating a serene and picturesque scene. It is considered a native UK plant as it grew in the UK pre the ice age era.

Bluebell (Hyacinthoides non-scripta)

A true emblem of British woodlands, the Bluebell transforms wooded settings into vibrant carpets of blue during spring. Its iconic drooping bells sway in the breeze, creating a breath taking spectacle that epitomises the beauty of the season. This native uk plant contributes to the enchanting charm of woodlands across the United Kingdom.

Cowslip (Primula veris)

Adorning meadows and grassy habitats with clusters of sunny yellow flowers, the Cowslip is a quintessential part of the country’s floral heritage. Its vibrant blooms not only add splashes of colour to open landscapes but also provide essential nectar sources for pollinators, enhancing biodiversity in these natural habitats.

Wild Primrose (Primula vulgaris)

A symbol of early spring, the Wild Primrose paints landscapes with its pale yellow hues, creating a soft and inviting atmosphere in woodlands and hedgerows. This resilient and versatile flower thrives in diverse environments, contributing to the visual diversity of the British countryside.

Dog Rose (Rosa canina)

The Dog Rose, a hardy and vigorous climber, graces hedgerows with its delicate pink or white blooms. A testament to its enduring presence, this native rose adds a touch of elegance to the countryside. Beyond its visual appeal, the Dog Rose also provides habitat and food for various wildlife, making it a valuable component of the ecosystem.

Civilisations and Introduced Plants

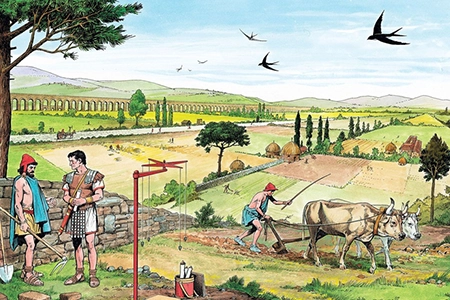

The Romans

The Roman impact on British flora is a testament to their influence on the landscape, introducing several plants that have become integral to the country’s botanical tapestry and are now mistaken for native uk plants. Aside from Nettles (Urtica dioica) and Roman Chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile), the Romans brought an array of plants for various purposes:

Apples (Malus domestica)

The Romans cultivated orchards across Britain, introducing apple trees for their versatile use. Apples provided a valuable food source, and their cultivation marked the beginning of the tradition of apple-growing in the UK.

Grapes (Vitis vinifera)

The Romans were known for their appreciation of wine, and they planted vineyards in different regions of Britain. While the climate posed challenges, this introduction laid the foundation for later vineyard cultivation.

Celery (Apium graveolens)

Romans brought celery to the UK, valuing it for its culinary and medicinal properties. Celery became a sought-after ingredient in Roman kitchens and gradually integrated into local cuisine.

Carrots (Daucus carota subsp. sativus)

Carrots were introduced by the Romans, not the orange variety we know today but a purple or yellow variant. Over time, cultivation practices led to the development of the familiar orange carrots.

Lavender (Lavandula spp.)

Romans cherished Lavender for its aromatic qualities. They utilised Lavender in bathing, as a fragrance, and for its purported medicinal benefits. Its introduction left a lasting impact on gardens and landscapes.

The Romans’ motivations for introducing these plants were multifaceted. Some, like Nettles and Roman Chamomile, served practical purposes in daily life and health. Others, such as Apples and Grapes, reflected cultural preferences and agricultural practices. The Roman legacy in British flora not only influenced culinary traditions but also shaped the horticultural landscape, creating a botanical bridge between ancient Rome and the UK.

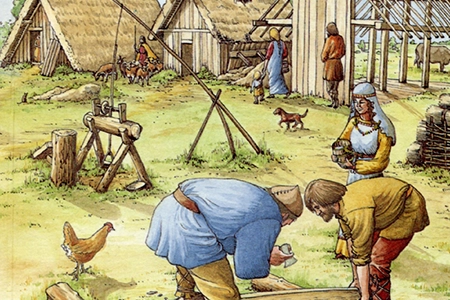

Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, who settled in the British Isles, significantly influenced the agricultural and botanical landscape. In addition to Barley (Hordeum vulgare) and Rye (Secale cereale), they introduced several plants that played pivotal roles in their daily lives and shaped the socio-economic fabric of the region and the perspective of those on the subject of native uk plants.

Wheat (Triticum aestivum)

Wheat was a staple introduced by the Anglo-Saxons, serving as a primary cereal crop. Its versatility made it a crucial ingredient in various food products, contributing to the dietary sustenance of the population.

Oats (Avena sativa)

Oats were another cereal crop cultivated by the Anglo-Saxons. They provided a source of nutrition and were used in various culinary applications, such as making porridge and oatcakes.

Flax (Linum usitatissimum)

The Anglo-Saxons introduced flax for its fibres, which were utilised in the production of linen. Flax cultivation became an essential part of textile manufacturing, contributing to the development of the region’s economy.

Hops (Humulus lupulus)

Hops were likely introduced by the Anglo-Saxons for brewing purposes. The cultivation of hops became integral to beer production, playing a role in the cultural and economic aspects of mediaeval society.

Chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium)

Chervil, an aromatic herb, was brought by the Anglo-Saxons for both culinary and medicinal uses. It added flavour to dishes and was believed to have various health benefits, reflecting the interconnectedness of agriculture and well-being.

These plant introductions by the Anglo-Saxons underscore their agricultural expertise and the profound impact they had on shaping the botanical diversity and cultural practices of the British Isles.

The Normans

The Norman influence on the British landscape left an enduring mark, particularly in the establishment of orchards. This horticultural legacy introduced several plants that became integral to both the culinary and cultural fabric of the region.

Apples are commonly mistaken as native uk plants but originally the Romans introduced apples. However, due to pillaging and destruction caused by invaders over the years, the production of apples became almost non-existent until they were reintroduced by the Normans.

Apples (Malus domestica)

Apples were a significant introduction by the Normans, contributing to the creation of orchards across the British Isles. The versatility of apples made them valuable for culinary purposes, from fresh consumption to the production of cider and other preserves.

Pears (Pyrus)

Similar to apples, pears were cultivated in orchards by the Normans. Their sweet and succulent fruit made them a popular addition to both sweet and savoury dishes, showcasing the Norman influence on the diversity of cultivated fruits.

Plums (Prunus domestica)

Plums were likely introduced by the Normans, adding another dimension to orchard cultivation. Plums were utilised in various culinary applications, including jams, jellies, and desserts, contributing to the richness of Norman-influenced gastronomy.

Cherries (Prunus avium)

Cherries found their way into Norman orchards, offering a delightful and flavourful fruit. Cherries were not only enjoyed fresh but were also used in baking and preserving, enhancing the culinary landscape of the region.

Quinces (Cydonia oblonga)

The Normans introduced quinces, a fruit with a unique flavour profile. Quinces were valued for their use in preserves, jellies, and flavouring, adding a distinct taste to the culinary repertoire of the time.

The establishment of orchards by the Normans reflected not only their agricultural expertise but also their desire to enhance the local cuisine and economy. Orchards, initially associated with the affluent, eventually became a symbol of the quintessential British countryside, shaping the landscape for generations to come.

Flora Often Misconceived as Native UK Plants

Rhododendron (Rhododendron ponticum)

Rhododendron, celebrated for its vibrant and showy blooms, is native to the Iberian Peninsula. However, its introduction to the United Kingdom occurred in the late 18th century. This non-native species quickly found favour among horticulturists for its ornamental appeal. The large clusters of pink to purple flowers create a picturesque display, but its origins trace back to regions far south of the British Isles.

Horse Chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum)

The Horse Chestnut, famed for its distinctive spiky fruit casing enclosing shiny brown conkers, is not indigenous to the UK. Native to the Balkans, this tree made its way to the British Isles during the late 16th century. While admired for its stately appearance and beloved conkers, the Horse Chestnut is a testament to the global exchanges of botanical treasures that have shaped British landscapes.

Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

Introduced to the UK in the mid-19th century, Himalayan Balsam is a conspicuous invasive species. Sporting pink, helmet-shaped flowers and explosive seed pods, it has a propensity to dominate riverbanks and damp habitats. Despite its invasive nature, this plant, native to the Himalayas, serves as a reminder of the unintended consequences that can arise when non-native species are introduced to new environments.

Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica)

Infamous for its invasiveness, Japanese Knotweed is easily recognisable with its bamboo-like stems and heart-shaped leaves. Originating from East Asia, it was introduced to the UK in the early 19th century. This aggressive plant poses significant challenges due to its ability to spread rapidly, impacting local ecosystems and even infrastructure and although its name is a tell-tale sign of its origin it is still mistaken for a native uk plant.

Cherry Laurel (Prunus laurocerasus)

A popular ornamental shrub, Cherry Laurel boasts glossy, dark green leaves and fragrant white flowers. Contrary to its name, it hails from regions in South-eastern Europe and Western Asia. The plant found its way to the UK in the 17th century, contributing to the diverse array of non-native flora that graces British gardens. While cherished for its aesthetics, its true origins lie beyond the British borders.

Defining Native UK Plants: Challenges and Influences

Defining native plants in the United Kingdom poses challenges rooted in historical complexities and evolving landscapes. The ambiguity arises from the dilemma of when to start the chronological clock. Should one adhere to the pre-ice age theory, considering only plants predating this era as native? Alternatively, must the assessment extend to the myriad influences over the centuries, including the Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman introductions?

The convergence of these historical influences, coupled with the continuous arrival of new plants over the centuries, further complicates the classification. The ebb and flow of human migrations, trade networks, and botanical explorations have continuously reshaped the British flora. As a result, attempting to pinpoint a precise moment when a plant becomes “native” becomes a fluid and nuanced endeavour.

Wildlife Benefits of Native UK Plants vs Non-Native Plants

A common misconception that pervades the world of gardening and conservation is the notion that only native uk plants contribute positively to wildlife, particularly pollinators. While native uk plants indeed play a crucial role in providing habitat and sustenance for local fauna, it’s essential to recognise the potential benefits that well-chosen non-native plants can bring to support biodiversity.

The assumption that non-native plants are detrimental to wildlife, especially pollinators, oversimplifies the complex relationships that exist in ecosystems. In reality, many non-native plants offer valuable resources for pollinators, including nectar and pollen. Bees, butterflies, and other insects often adapt to forage on a diverse array of plant species, irrespective of their origin.

Furthermore, introducing a variety of plants, both native and non-native, can extend the flowering season, providing a continuous food source for pollinators. This diversity helps sustain populations through different stages of their life cycles, contributing to overall resilience.

For gardeners and conservationists, this dispels the myth that cultivating non-native plants is inherently harmful to local wildlife. Thoughtful selection and careful planning can create a garden that supports a thriving community of pollinators, showcasing that the harmony between plants and wildlife extends beyond geographic origins.

In essence, it encourages a more inclusive and nuanced approach to gardening for biodiversity, emphasising that both native and non-native plants have a role to play in sustaining the delicate balance of ecosystems.

Non-Native Pollinator-Friendly Plants: Displaying Beauty and Biodiversity

Lavender (Lavandula spp.)

Many believe Lavender to be a native uk plant, however it actually originated from the Mediterranean but has seamlessly adapted to the UK climate, becoming a beloved addition to British gardens. With its fragrant spikes of purple flowers and silvery-green foliage, lavender stands as an aesthetically pleasing and pollinator-friendly plant.

Bees, butterflies, and hoverflies are irresistibly drawn to the abundant nectar-rich blooms, turning lavender into a bustling pollinator magnet. Its extended flowering period from late spring to early autumn ensures a sustained food source for pollinators, contributing to the harmony of beauty and biodiversity in UK landscapes.

Buddleja (Buddleja davidii)

Commonly referred to as the Butterfly Bush, Buddleja, native to East Asia, has found a welcoming home in the UK. With its arching stems adorned with clusters of tubular flowers ranging from white to various shades of purple, Buddleja lives up to its name as a favourite among butterflies, including the Painted Lady and Red Admiral. Its sweet-scented blossoms make it a popular attraction for a variety of pollinators during the summer months, adding both visual allure and ecological significance to British gardens.

Hebe (Hebe spp.)

Originating from New Zealand, Hebe is a versatile evergreen shrub that has seamlessly integrated into UK gardens. With varied foliage and showy spikes of flowers in hues of purple, pink, or white, Hebe adds both aesthetic appeal and pollinator-friendly features to the landscape. Bees and butterflies are enticed by Hebe’s nectar-rich blooms, and its extended flowering period from late spring to early autumn ensures a sustained supply of food for these essential pollinators.

Agastache (Agastache spp.)

Native to North America, Agastache, or Hyssop, has found a welcoming habitat in UK growing conditions. Characterised by spikes of tubular flowers in shades of orange, pink, or lavender, Agastache stands out as an attractive and pollinator-friendly plant. Bees and hummingbirds are particularly fond of Agastache, as it provides a prolific source of nectar.

Its aromatic foliage adds an extra layer of appeal to this plant, showcasing the potential for non-native species to contribute positively to the well-being of pollinators in the UK.

Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea)

Hailing from North America, Echinacea, also known as Coneflower, has become a well-adapted and cherished perennial in UK gardens. Its distinctive spiky central cone surrounded by vibrant, daisy-like petals makes it a visual delight. Due to its commonality it is often described as a native uk plant but it is not.

Bees and butterflies frequent Echinacea, lured by its rich nectar. This hardy perennial blooms from midsummer to early autumn, offering a valuable late-season food source for pollinators and enhancing the biodiversity of UK landscapes.

These non-native plants, thoughtfully integrated into garden landscapes, not only enhance visual appeal but also contribute positively to the well-being of pollinators without posing invasive threats and will live in harmony with native uk plants.

Expertise in Garden Design and Native UK Plants

At NGS, we bring decades of experience in garden design, plant selection, and overall plant knowledge to our clients. Our team understands the intricate nuances of native UK plants and how they can be artfully integrated into garden designs to create beautiful and sustainable landscapes.

When you choose NGS for your garden design needs, you benefit from our deep understanding of native UK plants and their ecological significance. We recognise the importance of selecting plants that are well-adapted to the local climate and soil conditions, ensuring their long-term health and vitality. We also have a vast wealth of knowledge on non-native uk plants that can be seamlessly threaded throughout your garden, offering a great range of benefits.

We consider factors such as biodiversity, pollinator support, and seasonal interest to craft gardens that are not only visually stunning but also ecologically resilient. By incorporating both non-native and native UK plants into our designs, we help create habitats that support local wildlife and contribute to the overall health of the ecosystem.

To find out how we can support you with your garden needs and queries visit the Contact Us page and get in touch. we can’t wait to hear from you!

Conclusion

The quest to unravel the native uk plants of the United Kingdom becomes a journey through time, tangled in the threads of historical influences and evolving ecosystems. While the pre-ice age theory offers a theoretical framework, the dynamic nature of human interactions continually introduces new botanical companions.

Acknowledging these complexities invites a richer understanding of the intricate tapestry that paints the landscape of native flora, reminding us that the story of plants is as much about their origins as it is about their journeys across continents and centuries.